China’s future is bright, and that includes conserving the past

For most Australians, mention of China probably does not evoke preserved buildings and landscapes in the way the English countryside does or the Italian centro storico.

But a new exhibition, Envisioning Historical Place, currently on display at the Tin Sheds Gallery in Sydney, suggests perhaps it should.

When China is evoked in public discourse in Australia it is most often as an engine of economic growth and miracle of modernisation. Its rate of urbanisation has become a source of journalistic wonderment and is sometimes depicted as a frightening juggernaut.

The consequences of urbanisation

China’s urban population (c.670 million) recently exceeded its rural population for the first time and the Chinese government expects 300-400 million more inhabitants to move to urban areas in the next 15 years. The environmental transformation represented by this process is almost unimaginable in both its scope and scale.

Such growth, of course, implies destruction, and historic places and patterns of dwelling have not been immune. The controversial Three Gorges dam project displaced more than a million people and destroyed countless archaeological sites.

Many historic, urban neighbourhoods have likewise been swept away in this unprecedented boom in urban and infrastructure development. But in recent years China has also made a very substantial investment in protecting and conserving historic places.

Heritage conservation at Tongji

The College of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University has been central to China’s expanding capacity in conservation. The exhibition Envisioning Historic Place testifies to the richness of place protection efforts underway in China and the great range of heritage documentation and conservation works undertaken by Tongji staff and students under the leadership of Professor Chang Qing in recent years.

Ancient China

Ancient sites, some of them inscribed as World Heritage, feature as one might expect.

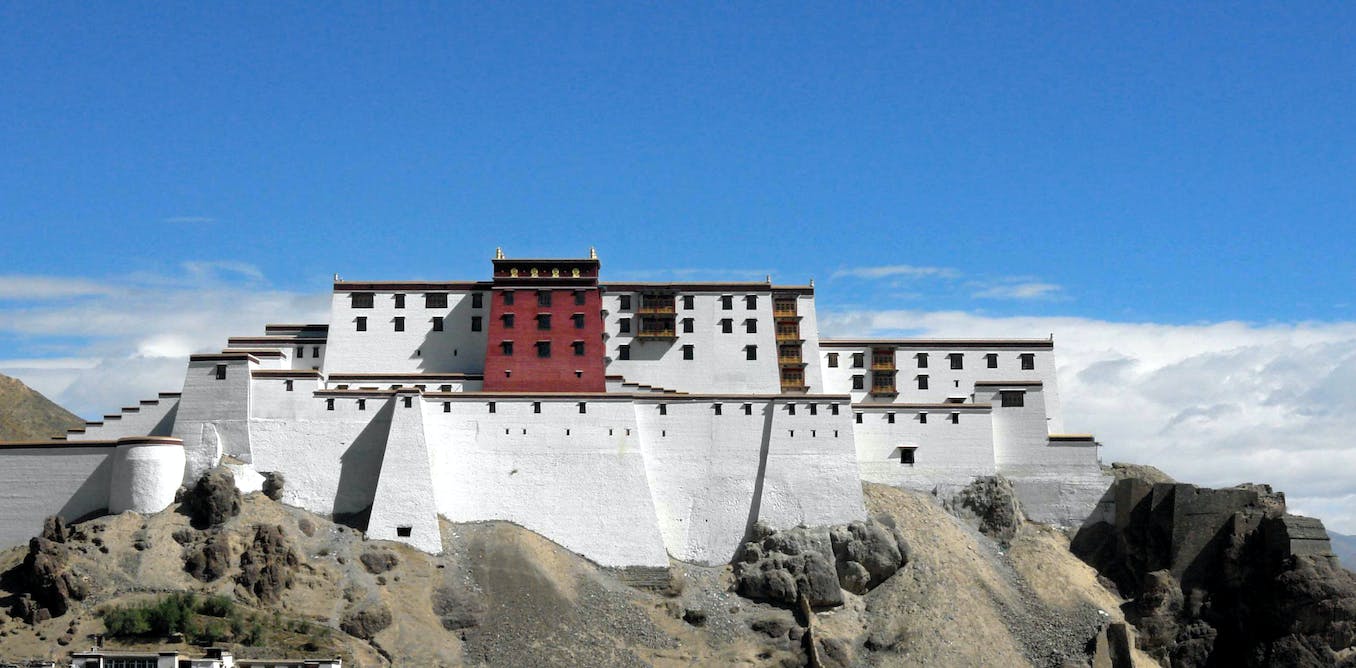

Professor Chang and his team have undertaken a major conservation and restoration project at the Sangzhutse Fortress in Shigatse, Tibet. This project involved significant repair and reconstruction of damaged and destroyed fabric. The aim was to reinstate the integrity of the fortress as an intact architectural monument.

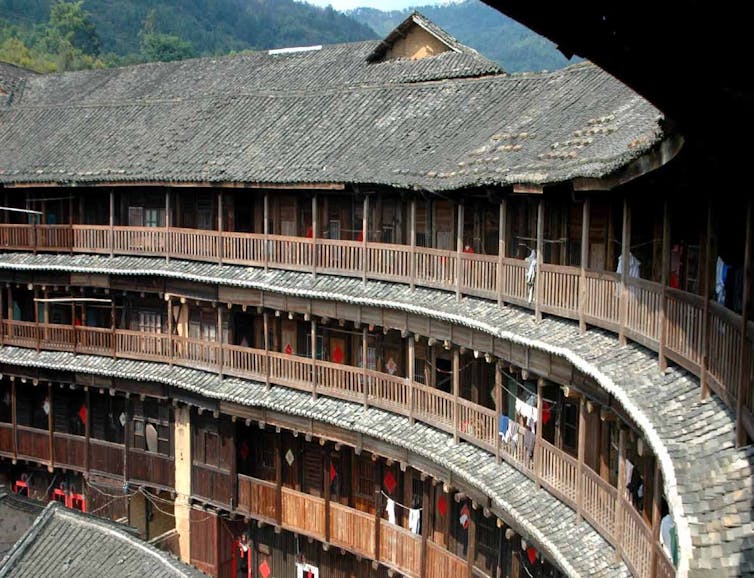

Members of the Tongji Planning and Design Institute – which is closely aligned to the College – have also created conservation plans and guided development strategies at the World Heritage-listed Tulou Buildings in Fujian Province, a set of earthen-walled, multi-story buildings that are used by the Hakka people as communal dwellings and defensive structures.

The Pingyao Walled City in Shanxi Province, which showcases five centuries of architecture and planning in Imperial China, is likewise the subject of a Tongji-devised conservation strategy.

Preserving China’s recent history

The scope of work on display in the exhibition reaches far beyond these symbolically resonant, formally-defined, ancient sites and includes a range of projects that affect the workaday built environment.

A Tongji team undertook conservation work on a group of houses in the Sinan Road section of the Old French Concession in Shanghai, an expansive district of late-19th and early-20th century urban fabric developed under French control.

They have also renewed a structurally expressive, concrete, university auditorium that was built in the early 1960s on the Tongji University campus and worked on the adaptive use of an obsolete 1980s-era power station in Shanghai.

But those are not even the most recent of the historically significant places represented in the exhibition. A team from Tongji was also instrumental in a project to preserve ruins in Sichuan province created by the devastating 2008 earthquake. This innovative memorial, developed in collaboration with local people, points to the interest in China today in deploying a wide range of modes and means for protecting and evoking the past.

Conservation at Tongji

The range of work and level of sophistication is striking given that the Tongji academic program in architectural conservation, China’s first such program, is little more than 10 years old. But it is underpinned by knowledge and expertise which is based on a longer tradition.

The College’s Historic Environment Survey and Record is a project that goes back to the 1950s – when staff and students in the architectural history and theory course began documenting China’s historic buildings, gardens and sites. Some of the most visually arresting material in this exhibition is derived from that project.

The beautifully drawn representations of Shanghai’s Yu Gardens, the structural section of an archway in Chang’s Manor – a Qing dynasty courtyard house – and the perspective drawing of the great atrium of the early-20th-century Shanghai Club on the Bund are all timely reminders of just how valuable such drawings can be in recognising the salient qualities of historic places.

The title of the exhibition, Envisioning Historical Place, alludes directly to the ambition at Tongji to go beyond traditional methods based in the conservation of architectural fabric and the preservation of construction techniques and craft skills involved in caring for old buildings.

These remain vitally important bodies of knowledge – but what the exhibition makes very clear is that a wider ambition is also needed, in which heritage conservation is a collaborator in making cities, in envisioning their historic spaces and linking paste and future.

It is an ambitious scope of work and impresses upon the viewer what can be done with concentrated knowledge and expertise within the university environment.

It will be fascinating to see in the future if this great concentration of expertise filters into the wider society and becomes a platform for civic engagement with the past and the development of both technical and historical knowledge in the wider architecture and planning field.

Envisioning Historical Place is on display at the Tin Shed Gallery at Sydney University until August 22.