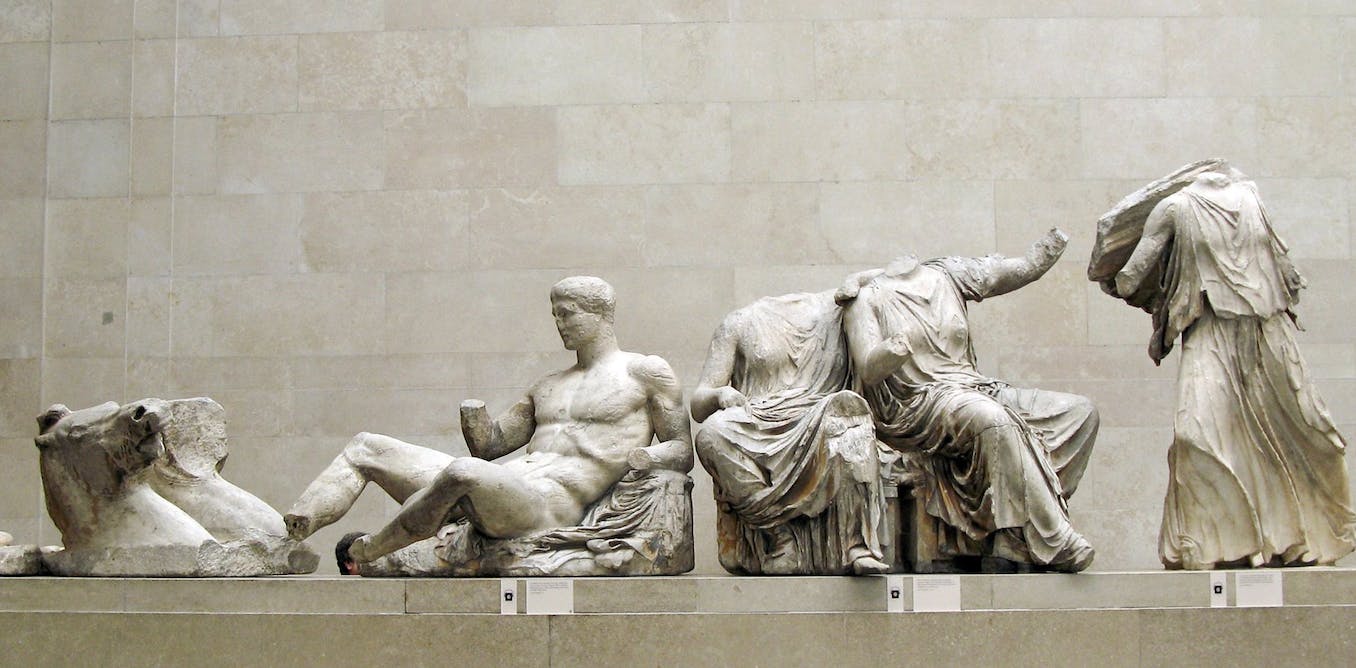

Sorry, British Museum, a loan of the Parthenon Marbles is not a repatriation

In the last few weeks, we have been regularly reminded that secret talks have been taking place between the Greek government and the British Museum over the return of the Parthenon marbles to Greece. As soon the discussions became public knowledge, a wave of optimism swept the media, culminating in The London Times congratulating the former British chancellor and chair of the British Museum, George Osborne, on brokering the deal. But as accolades were prematurely showered on the British Museum, I watched in astonishment and bit my lip.

As an international legal expert who spent the past two years working on the merits of the repatriation claim for my book The Parthenon Marbles and International Law, I had a sneaking suspicion that this was not it yet. Or was I missing something? The general euphoria must have been triggered by something grander than Osborne’s modest concession that “there’s a deal to be done” and his apparent willingness to loan the marbles to Greece? Surely by now we know better than to place our hopes in silky rhetoric of this kind that seems to make promises it has not made?

Apparently, we don’t. The need to make-believe is so strong that we grasp at the slightest opportunity and imagine that at last the marbles will be going home. The British journalist Andrew Marr recently captured this mood of exasperation in The New Statesman, when he called on the museum to return the marbles: “Give them back. For goodness’ sake, just give them back.”

Possession vs. ownership

If a loan is what’s on offer, then Greece cannot accept it. A loan would mean that the British Museum does not only possess the marbles but it also owns them – a beautiful illustration of the legal slogan “Possession is nine tenths of the law”, if you possess them, you own them. But Greece does not recognise what the museum does not have: ownership. The museum has nine tenths of the law. It has possession. And the museum knows that. An offer of a loan is a bait with consequences for the Greek claim under international law and the Greeks are right to beware of the British Museum bearing gifts. A loan is not repatriation and does not deal with the underlying matter of ownership.

Let’s stop hiding behind our thumbs. The dispute about the Parthenon marbles is not just about where they should best be located. It is also primarily a dispute about ownership. It is a dispute about rights and wrongs, and the need to redress a past wrong.

Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP

Heidelberg University and the Antonino Salinas Museum in Palermo have already handed to Athens the Parthenon fragments previously kept in their collections. In December last year, Pope Francis announced that the Vatican will be returning its fragments. The British Museum, which holds about half the surviving sculpture from the Parthenon, will have to follow their example. Does anyone imagine that 200 years from now, the Greeks will still have to clamour for the marbles’ return? I don’t. It is inevitable that the marbles will go home soon, although I don’t believe that the museum knows that yet.

Shifting attitudes

Both the museum and the current government continue to resist repatriation. But how long can they hold out against mounting opposition? Something has been fundamentally changing and it will become impossible for the British Museum and the government to cling on to the marbles for much longer. Attitudes internationally toward the return of cultural heritage have been evolving. Changing attitudes matter. They show that what was acceptable in the past, no longer is. Changing attitudes also shape international law. Societies evolve. The law changes in consequence.

Now is the time for the noble grand gesture, and it has the support of the British public. Ed Vaizey said it: returning the marbles would be “the big thing to do”. It would be the magnanimous thing to do.

Alternatives do exist. Remember what happened to Hans Sloane’s bust in the British Museum? Hans Sloane was the museum’s founding father, and his bust was once proudly displayed. But he was also a slave-owner. A scandal erupted a couple of years ago about the display of his bust in the British Museum. Oliver Dowden, then British culture secretary, warned national museums against removing contested cultural objects from their collections. And the British Museum responded: we will not.

Sure, technically, Sloane’s bust was not removed. But where is it now? It was quietly transferred to a glass cabinet, and Sloane was described as a slave owner. For two years, I lived on a London street named after Sloane, and for close to ten in a neighbourhood strewn with streets and buildings named after him or members of his family. I never gave it a second thought. I honestly had no idea who Sloane was. But now I know. The museum’s initial resistance to the removal of Sloane’s bust did more harm to it than swiftly taking responsibility and acting accordingly would have done. Welcome to changing times.

The future of deaccessioning under debate

A practical detail remains, a thorny issue of possible conflict between the government and the museum. How should the marbles be repatriated? Should national museums have the right to “deaccession” items in their collections on legal or moral grounds? In October last year, the government decided to delay the entry into force of two provisions of the Charities Act 2022 that would allow national museums subject to statutory bans on deaccessioning (the British Museum is one of them) to remove items from their collections on moral grounds.

Should the museum return them or should parliament pass an act transferring them to Athens? From a legal viewpoint, I’d much rather the UK government passed an act transferring the marbles to Greece. An act vested their curation in the British Museum. An act can send them back home. Better while it is still the magnanimous thing to do. With pomp. History will remember.